Coronavirus: the Haves and Havenots

It still irks me when I recall that someone told me I could not afford home grocery delivery. This happens to be the truth, but it was almost like telling me, "You can't afford to survive. You can't afford the life raft." I just wrote an article about how SNAP, the nation's food stamps program, is starting to roll out at-home deliveries in states like New York. This is a blessing for underserved communities which include the elderly, the "poor" and people like me. People whose income has gone up and down and is now down so they are on food stamps.

Everyone deserves to survive this pandemic. When I quit my position at a food market it was after spending a day cleaning shopping carts and checking out probably two hundred customers. I loved my customers (for the most part) there, but realized the next day that my life was at risk. One customer had even stopped to whisper, "Oh, you have to do the cleaning..." I smiled and said, "Yes, it's ok, I want to help and keep things clean and safe." That was true. But I also wanted us to be wearing masks, helmets, armor. I wanted things that at the time people weren't yet talking about, really. I wanted notices in front of the store warning people with temperatures not to come in and I wanted employee temps taken.

I am presently fighting for the right to collect Unemployment (part-time, because I also write part-time) and to have this expanded to all persons whose lives are threatened by a job. For those who choose to stay in a job such as cashier, they should be awarded hazard pay. Let's start with double, which would be $22/hour if you work where I used to in Guilford.

The news that several employees from ShopRite have tested positive and that other cashiers have actually died is a stark reminder of who joins first responders on the front lines of this pandemic. It's not all that dissimilar to who often goes to war - those who cannot afford to go to college or who see a financial safety net in the Army or Marines. On my last day of work a woman said to me, "At least you have a job." I thought, 'Would you say that if I were here working with Coronavirus? Or if any of us were?"

I spent four nights out of doors last June. Well, not really out of doors. I was at a train station with my cat because I did not have any place to go. It's funny how friends are few and far between if they think you're moving in. I was devastated by the loss of my mother and frankly, upon returning to the U.S. from grad school in London was in no shape to slide into a job. I actually remember those nights fondly because I had my sweet cat Wally with me. The weather was nice and we spent the days at places like the little waterfall in Milford. I took him to Cafe Atlantique and we sat outside. He pretended he was a dog. No matter how many résumés I sent out I could not convince people I was Trying my Best.

When I got the part-time cashier job I thought it would be more hours, and I was grateful for any work. I was starting, too, to finally get some freelance work. I tutored a little bit. I landed a real job interview in February, and then Coronavirus hit. Wally had died January 14, missing this period of history in the way the lucky miss flying bullets during gang warfare.

With all this time to reflect, I hope I can spread the word that suffering is a given for we humans but we are often forcing that on others without taking time to understand them. I hate to hear about "the homeless" as if they are a giant monolith. What about the 65-year-old former college professor who has no family and no means of support? What about the 70-year-old man who suffered from cancer and lost his life's savings? Or the 16-year-old runaway whose parents are beating each other up? It is so easy for society to just turn its back on these people. I was one of these people. I, with my Master's degree and my impressive clips from publications all over the world.

Let us please use this quarantine to no longer put divisions between ourselves and others. It's nice to donate to the local food bank, of course, but it's more important to adjust your minds: you, with your big kitchens and two months' worth of toilet paper, are no better than the 58-year-old journalist who lost her mother and had nowhere to go for four nights last summer.

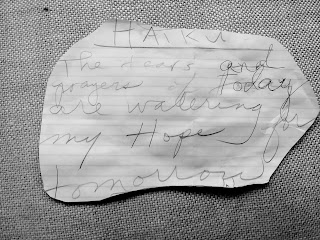

Image: Haiku by the author's mother, Kathleen Leonard, in her own writing.

Comments

Post a Comment